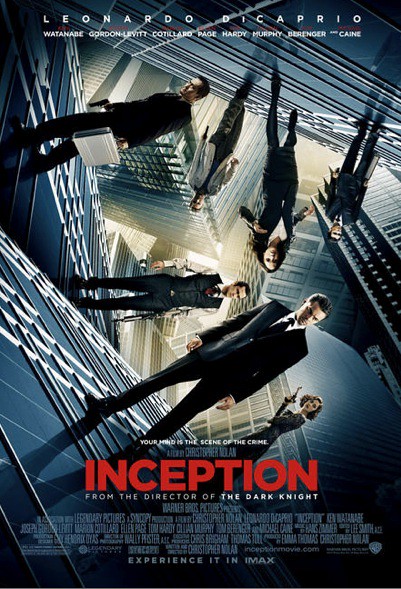

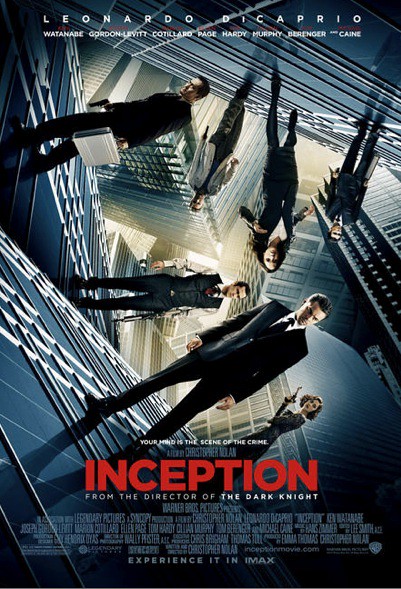

So after reading much of the criticism and meta-criticism and counter-criticism (and, let's be honest, meta-counter-criticism, and counter-meta-criticism, and so forth) and then seeing the movie

a second time, it feels like the majority of the talk centers on Nolan being more of an engineer of worlds, an analytical filmmaker more connected to his left-brain than a poet and dreamer, connected to his right. It seems the consensus among his detractors is that a film about dreams ought only be handled by the hands of a poet, the likes of Wong Kar-Wai, or David Lynch, or Jodorowsky, say. There has been a kind of weird serendipity in almost every conversation I've had since first seeing

Inception -- ranging from work conversations to writing conversations to criticism and discussions of

2001 to drunken rants in bars over whiskey, and even to a certain extent two unrelated discussions about love, sex, and relationships -- regarding the spectrum between cold analytical (left-brain) filmmaking/approach to life and less linear, sensual (right-brain) filmmaking/approach to life. I can't seem to escape the conversation, and because I find it interesting I haven't much tried. But I'll table that for now, and talk about the film, because that's why I keep this blog, right?

The thing is, within the rules of the movie, it's all very sound. It's a tight, controlled, brilliantly designed system we are given, with hard rules, specific consequences, and laws as elaborate and rigid as the laws of physics are (well, seem to be; the scientist in me won't let me declare so boldly what

is) that guide and govern the real world. And sticking to Nolan's laws, the movie makes pretty much perfect sense. The sense of dissatisfaction that I admit to having on first blush, and I think the sense of dissatisfaction the detractor-camp of critics seems to be feeling, comes from the fact that, quite simply, the way dreams work in

Inception is unrelated to how

my dreams work, to how probably

all dreams work, and this makes it feel untrue, or less real. The dreams of Nolan's fictional world feel entirely too real, too concrete, too stable. In actual dreams, you deal with fluid environments, inconsistent characters with shifting identities and roles and relationships, nonlinear events. In real-world dreams there is very specifically a lack of the physical laws which

Inception demands exist. If you accept the rules

Inception lays out, clearly and succinctly, even if they do not jibe with your ideas of how dreams go, then the movie runs like clockwork -- maybe even too much like clockwork. The problem is, this is the world of dreams laid out by architects and engineers -- both within the fiction of the story and within the real world. Ariadne and Cobb are architects. You have to admit, Arthur seems a touch engineery. He's certainly no poet. Eames and Yusuf seem aware of a right-brained approach to dreams, which actually shows in their approach to dreaming throughout (it's Eames who understands the psychology of the mark and it's Eames who is able to "forge" his own identity within the dream, not to mention conjure up Bigger Guns to fight off projections; and Yusuf is shown repeatedly enabling a hedonistic for-its-own-sake controlled dreaming). But they stand as a subtle contrast to the designers of the world, who clearly take after Mr. Nolan himself (Leonard di Caprio even looks like Nolan in this). The man who designed the rules that dreams "must" follow is a left-brainer through-and-through. The movie is a puzzle. It's not a dream. It's a puzzle. It just takes place in a (hard) science fiction world involving a fictional version of dreams. In that world, this is how dreams work. And to be fair: within those artificial guidelines, it has a lot to say about how dreams interact with us, how our subconscious both poisons us and sets us free, and how catharsis can be just as real in a

fictional world (like, say, a movie?) as it is in real life. I'm not taking credit for that last idea, I read it in one of the many reviews/articles, but it's a pretty solid theme here, no question. One of Nolan's points with the film seems almost like a direct refutation of the criticisms of it: it's just a movie after all, just a story, and not hemmed in by the dictates of reality -- but isn't that just as valid?

Still, I'm not entirely in defender-camp, because the movie

is a little dissatisfying, isn't it? The potential Pandora's box it opens up, moving through dreams consciously on a kind of action-heist mission, that could easily have been more dream-like, right? More like real dreams, I mean. Moments like the freight train barreling through the downtown metropolis, the zero-gravity and rotating-gravity combat scene, the beach with the crumbling structures like eroding cliffsides -- to my way of thinking these things actually become stronger if you

don't tell me what they mean or why they exist. If you told me the hotel hallway rolled simply because he dreamed it that way, or because he was losing control of his dream, that'd be enough for me. If you told me the train was there simply because this is a dream and obstacles are obstacles, that'd be enough for me. Making the gravity directly related to the physical activity of your sleeping body's surroundings (especially when you're asleep in another dream, one layer up) is less fun than just saying, "it's a dream, and it means disorientation, fear the world can betray you, loss of control, or whatever else it might mean to you." Making the freight train a painful memory of how Dom and Mal committed Limbo-suicide is actually less moving to me than just saying, "it's a dream, and it means massive unstoppable forces, penetration of stable channels, loss of control, or whatever else it might mean to you."

If you don't literalize every little thing, your story about dreams becomes more than merely a puzzle, it becomes a poem. But as it is,

Inception seems more than happy to remain just a puzzle -- albeit a fucking good puzzle, and it's actually got better drama on second watching, I must admit. Very movie-ish, very Hollywood, and very (how can I not say it?) left-brained, but not without emotional punch. Seeing Mal as

only a projection redefines her in my mind, and while I can't find motivation for many of her actions (like allying herself with Saito in the opening dream) I understand how to hear her interactions with Dom and Ariadne, and it's so much more painful when you understand that this is just Dom's inner self, a sort of worst-case-scenario deepest-fears-realized devil on your shoulder, talking. It's heady stuff. But yeah, that's pretty much it: heavy on the head, light on the heart.

If you accept that, it's pretty brilliant. If you can't or don't want to, then it feels a bit like a missed opportunity. I've never been able to honestly decide if I'm a right-brained or left-brained person, leaning so heavily one way or the other in different regards (and not a fan of binary classifications in general), so maybe that's why this movie feels to me like both: brilliant to my inner engineer, and a missed opportunity to my inner poet-dreamer.