Now that I've seen it once and read copious reviews and critiques of it (in defense of as well as criticisms against it) it's hard not to remember some of those comments when rewatching it. The thoughts in this review especially stick with me, like pointing out the lack of rich character actors and the flatly unpopulated world around our heroes, and the opinion that the epilogue seems to undo the story.

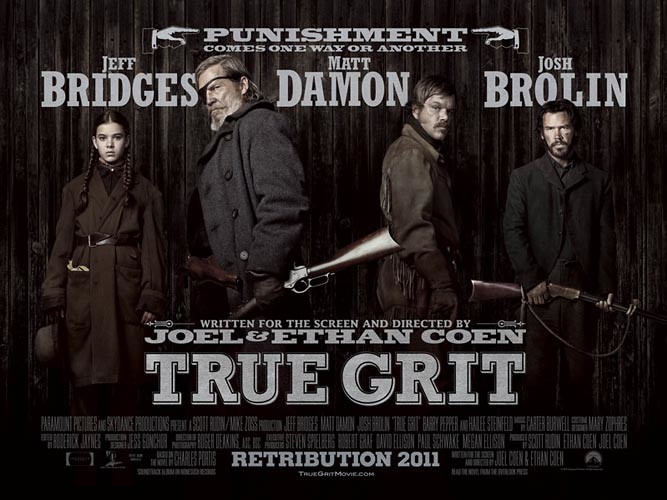

At first, I felt I agreed entirely with the two comments. For one, the Coens are usually the very best character-actor casters in the business, and every walk-on in every film usually feels distinct and well developed, but here it's hard to deny the dearth of developed bit parts. The auctioner, the funeral man, the bear-headed dentist, the young man shot in the leg, everybody feels a little Coenesque (Coeny?) but nobody feels as fleshed out or gorgeously quirky as the gas station man in No Country For Old Men or the girls telling Marge about the "funny lookin'" guy from Fargo. But then I started to think, maybe (surely!) it's not an oversight: maybe it's to keep the emphasis of the story on Mattie, Rooster, and La Boeuf (and to a lesser extent the antagonists of the story, Ned Pepper and Tom Chaney). Dramatically, it's a road movie about three distinct characters all chasing a man who's done wrong. Dramatically, the interplay between them and the intricate mismatches of their desires drive the story. Thematically, they each have different representative motives for chasing Chaney: Mattie represents direct eye-for-an-eye vengeance; La Bouef represents the law; Rooster Cogburn represents mercenary killing. One hunts for family/personal reasons; one hunts for legal/community reasons; one hunts for the value of the prize. That's oversimplifying, but the dynamic exists whether or not I overcategorize things. The point is, both dramatically and thematically, with such a simple story, it might actually muddy things up and diminish the impact if we gave too much credence to the world around these three. Or anyway, that's a thought.

And then there's the end. [SPOILERS!] I'm really just not sure what to do with it, but to be fair I felt that way about No Country at first, and the only way I got over it was to let go and allow it to be what it is. The "missing reel" ending of No Country For Old Men, in which Llewellyn dies offscreen, demands you accept it without justification, and that feels like part of the message. Similarly, the "quarter century is a long time" denouement to True Grit seems in part to exist specifically to undermine and subvert all or most your assumptions about how "these kinds of stories" are supposed to end. In fact, the tone shift begins earlier, and is much more gradual. I'd have to see it again to say for sure, but I think it happened just after La Boeuf shot Ned Pepper and got brained by Chaney, and just as/before Mattie murders Chaney for killing her father and tumbles backward into the mine shaft. From that point on, the plucky-adventure tone fades away and -- just when you assume the mission is over and the heroes can all rally together, congratulate each other and begin the long journey home -- things get, for lack of a better word, real. The romanticism dissolves and the viscerality and mortality of the old west rears its head. What looks like a solution to her problem (the soldier's desiccated corpse and the shiny knife in his belt) proves much deadlier than expected, as her would-be savior's chest cavity is full of writhing, just waking rattlesnakes. Before Cogburn (almost literally appearing out of nowhere) can save her, transformed from one-eyed drunken oaf into knight in shining armor scaling down into the well (rather than up into the tower), Mattie is bit, and despite efforts to suck out the poison (this itself a visceral and frightening moment that feels like a dash of "realism"), there's nothing to be done.

And so Cogburn abandons La Boeuf on the cliff face, dazed but mostly all right (and this is the last we will see or hear of him; even Old Mattie does not know if he ever came down the mountain alive), and races her pony Little Blackie wildly back toward civilization. The ride is exhaustive, and in order to keep Blackie racing at full speed, ignoring the horse's own failing body, Cogburn stabs him in the flank. This only buys them a little more time, however, and eventually thee horse succumbs and collapses with them on it, and Cogburn is forced to euthanize the animal with a single resounding shot. (Last time I talked about the crucial role guns play in the story; here is another example, the gun as brutal mercy.) Each step of this arduous journey back to civilization is harsher and harder to accept than the step before it, each showing a little more cruelty and coldness in the world. And to top it off, even when Rooster Cogburn carries her in his own arms the rest of the way, collapsing about twenty yards from the door and firing his gun (!!) to wake the inhabitants of the cabin, it wasn't nearly enough. Mattie loses her arm. Cogburn disappears away, to die some twenty-five years later as part of a traveling roadshow parody of the man he and others (like Cole Younger and Frank James) once were. Mattie grows up with the same hard-minded, icewater-cold demeanor, and at some point between fourteen and forty that stops being charming. One-armed and slightly shrewish, she never marries, misses her chance at reconciliation with the men with whom she'd bonded so beautifully, and presumably dies alone. And that's your ending, as unromantic and stark as you can get.

According to the review-link above, this end suits the book because the book is told entirely from Old Mattie's point of view and in essence, part of the story is that the joke is on her, our unreliable narrator. But here we do not know Old Mattie, and the actress is frankly kind of a lump who speaks only two or three short, curt non-voiceovered lines, and so the ending can't help but feel jarring. Again, maybe (surely?) this isn't an oversight or accident. Maybe (surely!) the Coens knew just what they were doing -- in fact, it is hard to imagine otherwise. So I have to assume this conscious de-romaticization and distancing is part of the point here, and that like the "missing reel" in No Country For Old Men, we are absolutely meant to have our assumptions denied and yet our dramatic expectations answered. If you include here the (wonderful) ending of A Serious Man, it's clear with their recent films that the Coens are confident enough in their storytelling that they want to leave you on very unsure footing when you walk away. These are not certain worlds with easily tied-up endings and convenient morality, but neither are they chaotic worlds with unraveling loose-ends and nihilistic moral anarchy. In fact these are carefully messy worlds that reflect just what the Coen Brothers want to reflect from our world.

So I guess the bottom line is, I can't quite dismiss the criticisms people have raised against this film, though maybe I can see some logic behind the choices made. Also, like those raising the criticisms in the first place, I do think this is an undeniably amazing film, but they have set the bar so high with their last two that True Grit can't help but feel simpler, plainer, and more straightforward, even with some of the challenging choices made. It's hard to complain about filmmakers making a couple of movies so good that their follow-up can't quite top it. Maybe it should be said, it was wise of them not to try.

Seen at the Regal Fox Tower.