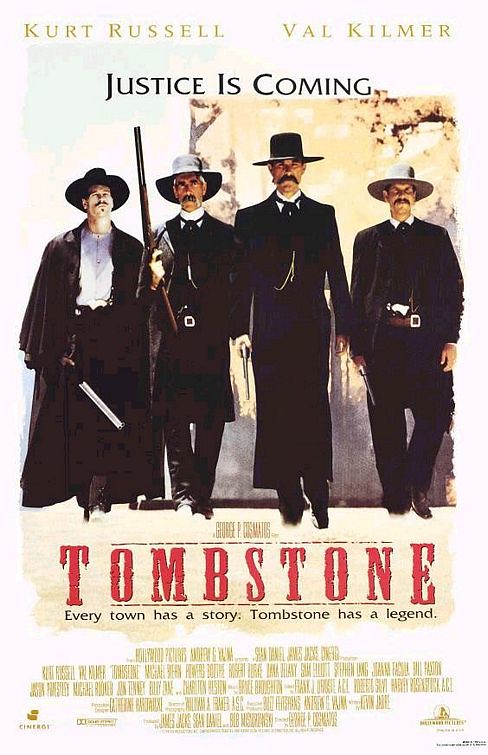

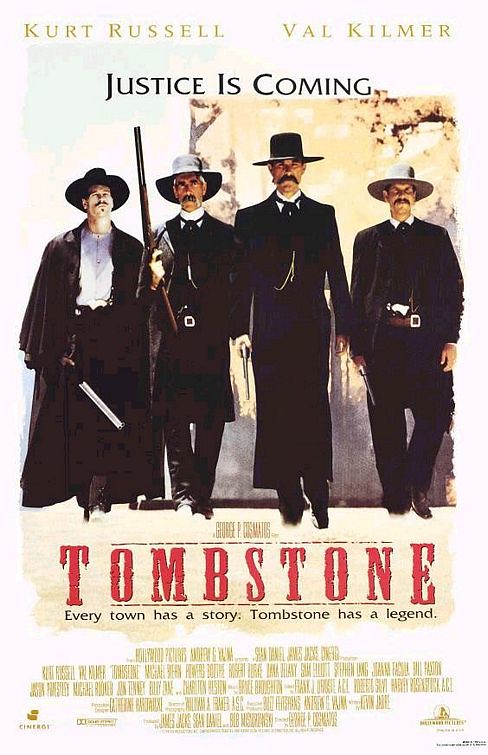

Boy, it is hard for me not to view this in the shadow of it's successor,

Deadwood, which admittedly owes it a great debt. This film is so proto-

Deadwood at times it's amazing. It's even got Trixie and Cy Tolliver. Actually,

Tombstone has just about everyone in it, and that's a bit of a problem, but I'm getting ahead of myself.

I have a couple of friends who name this among their favorite movies of all time, so I feel a little bad saying this, but this didn't really work for me. Parts of it did, to be fair, but not enough. The story just never came together meaningfully for me. For one, the story opens with Robert Mitchum telling me that the Cowboys with their red sashes are America's earliest organized crime and that they are feared far and wide, but over the course of the story they aren't much more than a ragtag bunch of drunk thugs and bullies. In fact, for the first chunk of the film they are shown as completely integrated into society, and sure they're rowdy and obnoxious, and have a tendency to fire off their sidearms for no reason, but these guys are more like Biff Tannen and his gang than Don Corleone and his. To make matters worse, Wyatt and his brothers are just as bad, bullying their way into gambling money, picking up and putting down the badge whenever it suits them and their righteous demands. They all waffle when it comes to actual gun-violence, talking a big game but hesitating to step up, but then again so do the Cowboys (except for two). Maybe there's a reason the outlaws are called Cowboys and the heroes are shown to be a gang themselves; maybe

Tombstone is trying to tell me that the only difference between a murderer and a lawman is a badge. I'd accept this as a good and interesting (and revisionist) theme for a western, except that it's never played that way in the characters' stories. I'm supposed to feel terrible when Morgan Earp dies and triumphant every time Ike Clanton cowers and begs not to be killed for his (admittedly violent and anarchic) tomfoolery. The movie could not give a more triumphant reward to Wyatt Earp if it tried, but again I'm getting ahead of myself here.

Before I talk about the end, I want to talk about the proto-

Deadwood thing again. This movie -- there's no other way to say this -- has too many characters doing too many things. It seems like every other character is a subplot or side story. And you can't throw a rock in Tombstone, AZ, without hitting a brilliant character actor being underutilized by the baroque script. In fact, there are so many heroes, villains, love interests, lawmen, businessfolk, townfolk, thespians and thugs that many of them are literally written out, killed off-screen to minimize the clutter as we near act three: Terry O'Quinn the mayor, Billy Zane the actor, and that girl from

Fletch who plays Wyatt's unloved wife all get passing snippets of dialogue to explain their deaths, and Jason Preistley as the openly gay tagalong to the Cowboy gang who becomes a dirty lawman is so moved by Zane's death that he wanders off out of the story, declaring that the town needed "some kind of law," and leaving that fruity county sheriff to presumably die during the --

-- okay, now let's talk about the ending. This film has two main antagonists. One is the brilliant Powers Booth as the gang's leader Curly Bill (who, proving he's more Biff than Corleone, goes on an opium-fueled shooting binge and is saved from a lynching by Wyatt himself, who still insists he's not interesting in lawmaking; this is but one of many strange encounters that ought to enrich the relationships between "good guys" and "bad guys" in the story, but really only seems to muddy the waters about who's dangerous and who's an ineffectual laughingstock). Curly manages to get the drop on Wyatt and his gang (oh, and his gang? Consumption-riddled Doc Holladay and three members of the Cowboy gang who suddenly decided their gang was too mean and rather than leaving town to avoid more violence swore allegiance to the Cowboys' bloodthirsty, revenge-obsessed adversaries, the Earp gang). Then Wyatt decides, literally, that he's had enough of being locked down in a crossfire and firing helplessly into the trees, and so he

stands up and walks out into the river and goes all RoboCop on everybody, dodging every bullet without even trying and killing most of the gang before shotgunning Curly Bill to death.

The other antagonist is the meaner and significantly less developed character of Johnny Ringo, played by Reese from

Terminator. Ringo is so mean that only someone as late-game-Faustian as Doc Holladay (more on him in a second, and that'll be, I think, my last bit for this mega-rant) can see into the enormous hole of his soul and understand the man. Ringo calls for a one-on-one with Wyatt, but Doc sneakily fakes being even more dying than he really is so he can get there first, and Ringo tries to capitulate (especially when Doc says, "hey check this shit out I'm even a fucking cop now y'all still want a piece of this?" -- of course I'm paraphrasing) but Doc won't have it, and after fuckin' with him for a bit he puts a bullet into his skull and then challenges the dying, no doubt confounded and frustrated new gang-leader to euthanize him. (Doc is dying, remember, and earlier told Ringo that he'd be a daisy if he could be the one to do him in; when he cannot do it, Doc says contemptuously, "You're no daisy.")

So we have two villains, and each is dispatched without much difficulty. The actual scenes of their deaths are okay, but neither feels like the ultimate face-off kind of action/western showdown you expect, or that we're supposed to pretend these characters deserve. Once that's done, as there are still obstacles to take care of, like an enormous "gang" or "organized" criminals -- whom I've never seen sharing a profit or respecting a hierarchy, unlike say Wyatt and his mean -- so we have a post-showdown montage sequence,

a fucking montage sequence, in which the rest of the gang is brutally chased and murdered, except that weasel Ike who denies his colors and swears tacitly he's done flying the red sash. But

then the movie's not over, because we have to have a sort of triumphant-cum-tragic death scene for Doc that's not half as sad as it thinks it is but not half-bad either. Oh, and

then we jump ahead to Denver, to see the sadistic, trigger-happy mass murderer Wyatt Earp cavorting happily in the snow with his actress ladyfriend, the pre-feminist who really opened his eyes up about how strong a lady can be when he spent exactly one scene with her, a chaste picnic in the flowers, before shunning her openly in the rain (in front of his wife). It is to this woman that he promises his undying love. In case you were thinking, "hey what the fuck dude, you're married and sure she's a junkie but you did kinda seem to be into her earlier plus you've got to be a rough person to be the wife of so who can blame her?", well along comes Robert Mitchum's voice again to tell us, oh right she died off screen too, so it's okay. And Ike died. But Wyatt and this woman (Dana Delaney, by the way; another great underutilized actor), they get the happily ever after, moving to LA and getting a hero's funeral 47 years later with weeping movie stars and the whole bit.

The moral here is clear: If you march into a community with superior forces, take over the government through scheming and brutality, and kill everybody everywhere who is a threat to your power, you just might die a hero with weeping movie stars.

I did say I wanted to mention Val Kilmer's Doc Holladay. I desperately wish this had been a bit more arty and a bit less actiony and had focused on the smarmy, deadly-but-dying Doc Holladay. What a character! A gentleman killer, a cad, a card shark and heistman who partners up with his old sheriff buddy (further highlighting that the good guys are the bad guys in this particular story) and, like Wyatt says to him on his deathbed, is less of a hypocrite than he pretends; he only likes to look like one. Doc Holladay's sweaty, sunken good looks were so beautifully exotic in the dusty, bearded, manly world of the Old West, and his proclivities toward education, sarcasm, and culture, while still being a fully capable and fully willing gunslinger of his own -- all make him an infinitely more interesting and attractive character to follow than the thug with the silver star named Wyatt.

Oh well. Honestly, I didn't hate this movie, it's got some very good dialogue and a couple of great characters. I just saw it as kind of a mess, with too many things going on and a seriously confused sense of morals and propriety. It's still fun, though almost every way I'd call it fun

Deadwood runs farther with and has more fun with. But as for Hollywood 90s re-revisionist westerns,

Unforgiven is still the top of my list.