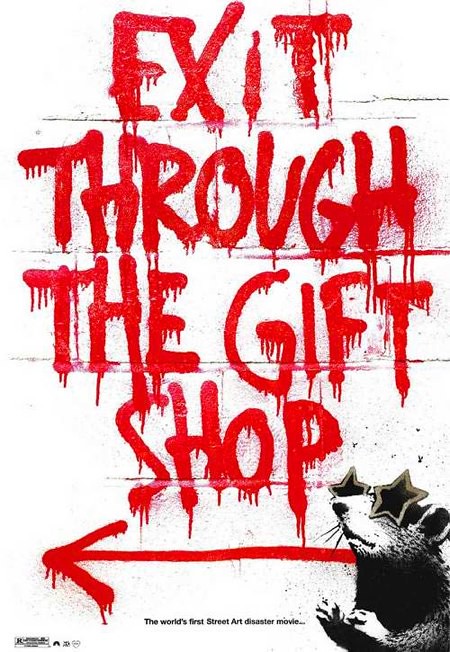

Boy, 2010 really was the high-water mark for the documentary/mockumentary/hoax ambiguity, wasn't it? Between Catfish and I'm Still Here and this, it seems like the best way to make a doc was to make it meta and question not just itself but the viability of the medium. The documentary genre has seemed muddied up by a confusion of facts versus truth (or worse, factoids and opinions and soundbytes versus truth), and if we've hit a point where we can bust that journo-evangelistic style wide open, I'm all for it. But whether or not it's the genuine article, that's not what Exit Through The Gift Shop is aimed at.

Exit busts wide open a different pet issue of mine: the disparity between art, artists, and the art scene. It posits that there are those who make art, that there are those who call themselves artists, and that there are those who land on the art scene, and is shows us really clearly that we are wrong to assume a natural crossover between any of the categories. At first the film was gripping and engaging, but when Banksy turned everything upside down -- when he disappeared behind the camera and Thierry took the role of underground sensation -- the film suddenly felt like some kind of personal-artistic-integrity agitprop, and I found myself more and more aggravated by the bland, voiceless shit "Mr. Brainwash" was selling the world.

Someone (Shephard Fairey, maybe? or actually I think it was Banksy himself) pointed out rightly that Mr. Brainwash is the 21st Century Andy Warhol. He has a team of artists mass-producing his half-baked ideas, which are basically just juxtapositions of recycled pop-cultural iconography. The difference then is that the 20th Century Andy Warhol was semi-knowingly making a statement about the nature of scenes, fame, celebrity, and popularity, and he was selling the idea that he could sell art as much as the art itself; and the 21st Century equivalent, the post-postmodern, the post-information-age, post-meta Mr. Brainwash, seems to be exploiting the now-commonplace abusably tenuous nature of scenes, fame, celebrity, and popularity.

All art scenes are full of half-assed, idea-less recyclers in love with themselves or just desperate for a scene. And whether or not the film has been scripted for our benefit or caught and cleverly cut to tell the story it does, it still does a wonderful job of not just exposing that, and deriding it, but steering (mostly) clear of a holier-than-thou attitude about it. The line between what Mr. Brainwash did on the streets and what Shephard Fairey did is largely a matter of who got there first and who made the bigger splash doing so. Fairey seems infinitely more aware of his position and of his statement-of-purpose, but there's some fuzzy area in there, and it's hard to know for sure if Thierry Guetta is being edited to make a point or if he's truly a moron. The line between MBW's art show and Banksy's LA art show again seems to come down to a matter of awareness and who got there first with regards to controlling and riding one's own hype. Again, it's hard to say for sure editing doesn't play a part here, as we linger on the selling-a-hollow-man aspects of Brainwash's promotion but emphasize the successful celebration that was Banksy's show. (The two shows are demonstrably very different; but how different is difficult to know.)

Mr. Brainwash is every bad artist, aping what he's seen and skipping from art fan to would-be art giant without taking the time to hone and develop, and the film does seem to vilify that attitude (which I happen to agree with). What it doesn't touch on, probably smartly, is the nature of artistic voice, intent, or talent. Fairey and Banksy seem to have things to say, and (lesser artists?) Invader and Swoop and Borf and most the others have at least the distinction and singularity of style. The film doesn't try to tell you why what works works. It just shows you that the fact that it works doesn't necessarily mean shit. Art scenes and art critics are capricious mobs, racing each other to the next big thing. That kind of desperate fickleness leads to a throw-everything-at-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks mentality, the opposite of a steady, discerning eye. In other words, it's not very surprising that someone like Bush or Linkin Park might become huge rock stars, and it's not very surprising that someone like Mr. Brainwash might sell a million dollars worth of street-art knockoffs. At least a couple of other, "more real" artists like Shephard Fairey and Banksy can help us laugh at it while they exploit it, right?