Everything below is spoiler heavy. You should know that.

I shouldn't be surprised that a Gaspar Noé film is more interesting as provocative art than it is as dramatic entertainment. The experience of the movie is at times exhausting, overstimulating to the point of discomfort, and tedious in its obsessively circular narrative and thematic directness. The aerial floating and shaky POV camerawork leave one dizzy (hardly by mistake). Each shot is bursting with oversaturation, and any time something can strobe, it does strobe. Being behind the protagonist's head or spending fifteen minutes at a time roving and blinking in their as-literal-as-possible POV made me anxious and eager to move to the safer ground of third-person cameras that don't rotate, float, distort, or stare straight down at everything from an impossible, dizzying height. But of course, that's the point of it all, isn't it? I'm supposed to feel my nerves jangled, my safety net removed. I'm supposed to get antsy and agitated. That's why it's provocative.

And so saying, despite the discomfort that comes with it, I can allow it. What makes the film hard to get behind is the story, which I generously (but perhaps not tactfully) referred to as "Gaspar Noé sucking Sigmund Freud's dick." It's all about mother's breast, confused familial sexualities, and spiraling inward, almost literally into and out of one's own navel. It couldn't be any more obvious about its love of Freudian complexes if it tried. They are telegraphed in every relationship in the story. The day before the story begins Oscar's nerdy best friend Victor (Oscar's foil/surrogate mirrored self?) discovers that Oscar has been fucking Victor's mom. Later in the film, we match cut from young Oscar spying on his parents doing it doggy-style to adult Oscar spying on his sister fucking his mentor/friend Alex doggy-style. Basically the story exploits sexual desire with your mother and with your sister every chance it gets. I'm normally a big fan of cleverly used archetypes, even outdated ones, because you can get a lot of dramatic and philosophical mileage out of the same old playing pieces if you do it right. But here, they were just too obvious and too for-their-own-sake for me, and I found myself groaning at the drama. It's... well, a lot of it is dumb.

But not all of it. I want to give some credit where its due here. Follow with me. So the set-up goes, Oscar is mad in love with his sister Linda. (I understand that they are all each other has after losing their parents as children in a brutally depicted car crash, but it's pretty tough to understand why anybody would love someone as emotionally and mentally stunted as Linda. To be fair, Jen nailed it on the head by pointing out: she needs him. Case closed.) So when he dies -- the roundabout result of the drug dealing he did to "save" her by flying her out to Japan -- he does the directly-referenced Tibetan Book of the Dead thing and sticks around as a disembodied floating camera-eye. He obsesses over falling into lights, chases the things he cannot let go of, and vaguely seeks out reincarnation while basically stalking the sister he's in love with. So even before Linda pees on a stick and it turns up positive (in Japanese), I think pretty much everyone in the theater had predicted that his final reincarnation would be as his sister's baby. But the movie anticipates that and subverts it. Oscar tries to become his sister's baby, but we see him spiral out of her bare belly mid-abortion, foiled by her lack of interest in having a child. He even, after roaming around miserably, returns and tries again to enter the aborted fetus, the camera spiraling in and passing through the graphic remains. Oscar did try it, just as we knew he would, but instead of it being an ironic twist, it was a failed attempt, too easy, too obvious. The character wasn't going to get off that easily.

And so the story continues, the drifting becoming even more miserable and exhausting than before, until Linda and Alex are in a cab that does a headlong into a semi-truck, almost exactly like how Linda and Oscar's parents met their demise so many years earlier. From this point on, the disorienting movie becomes even more disorienting, as we drift away from neon Tokyo and into a sort of even-more-neon version of Tokyo, which we recognize as a massive blacklit model Alex's friend had built earlier in the story. It is fantasy Tokyo, with a massive Love Hotel at its center which Oscar had fantasized while high about being able to float into and see all his friends having crazy sex. And so here at the end, we spend a long, long time doing just that. So long, in fact, that I grew tired and bored of all the sexual bodies, whose genitals glowed with tendrils of light. Anyway, after an exhaustive sequence of drifting through rooms, we land on -- guess who -- Linda, alive and well, fucking a man and asking him to come inside her. Now ghost-Oscar can do what he wanted, and he drifts inside, catches a ride in a sea of semen (yep) and when that one spermatozoa pops inside the egg, he is there, reincarnated finally as Linda's precious baby. The last shots are a little moving in their "this must be what being a newborn baby would really seem like" blurriness, but there's something just a little too obvious about the comfort of mother's nipple, and that the wailing and crying doesn't begin until the moment the umbilical is cut and the baby is carried down the hospital corridor. It's as subtle as a sledgehammer.

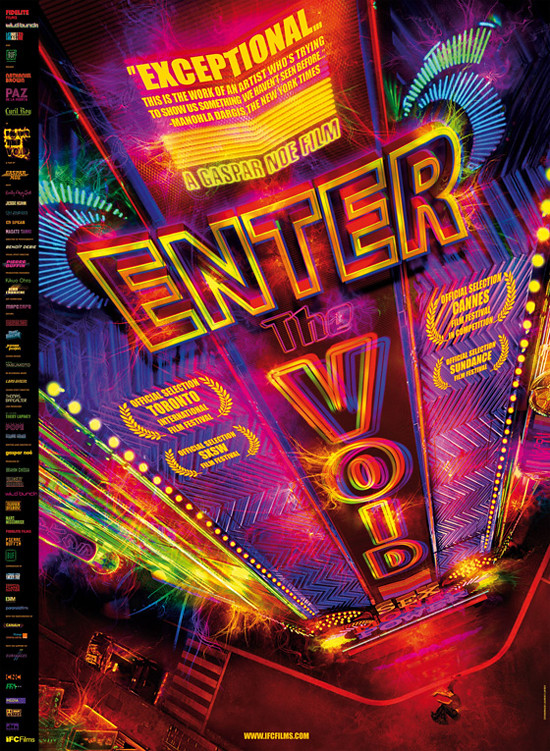

I want to say it's nice that the story had, under all its layers, a protagonist who wanted something, had obstacles, and found resolution (and I'm totally okay that the resolution came bitterly, in the form of an obvious inward-turning fantasy). But I can't pretend that the movie isn't 137 minutes long, and I can't pretend I didn't use the word "exhausting" or synonyms for it half a dozen times in describing it. Dramatically speaking, it's got two clear choices and a lot of backstory exposition, cleverly (enough) delivered. Dramatically speaking, the pay off isn't worth the investment. But there's something in here, a philosophical and metanarrative message that has slightly higher dividends. Which brings me (appropriately) full circle here. As a story, as drama, as entertainment, Enter The Void feels lacking. But as art, as a challenge from a provocateur to experience things differently and to look at the world with new eyes, as an exploration of big subjects like sex and death and storytelling, Enter The Void is an interesting (if exhausting) experience.

Seen at Cinema 21.

No comments:

Post a Comment