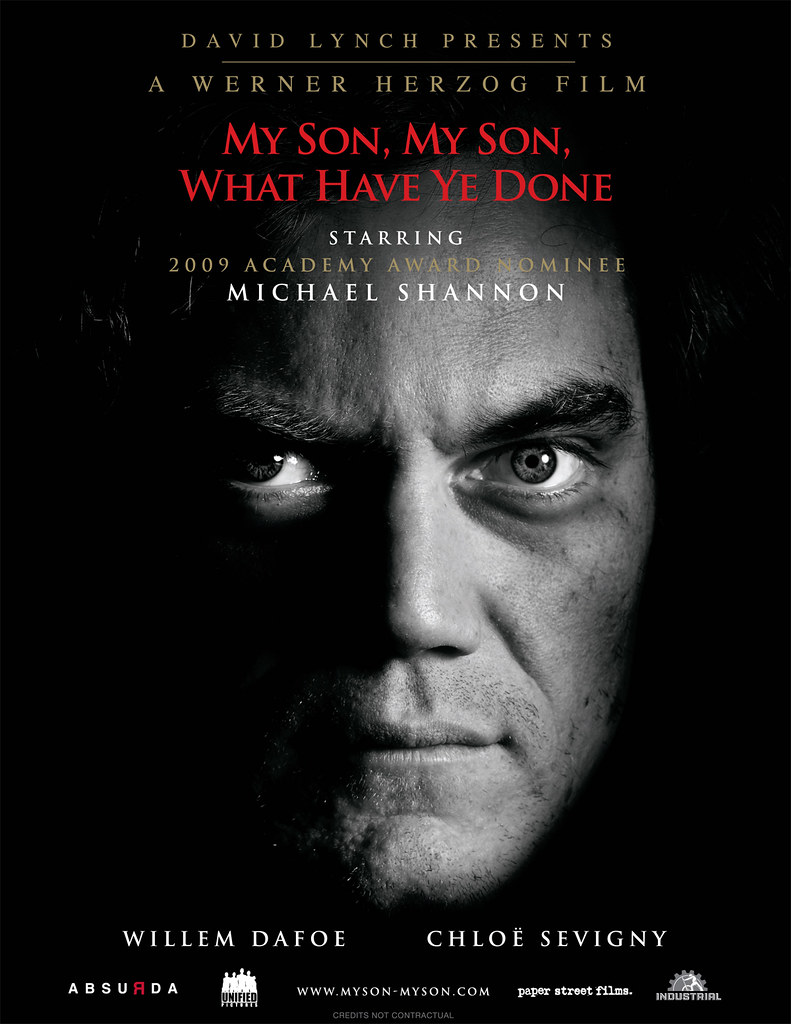

As soon as I heard that David Lynch was executive producing a not-quite-murder-mystery film by Werner Herzog I knew I had to see this. Reports that Michael Shannon was basically channeling Klaus Kinski didn't hurt either. Five minutes into the film, this felt like everything I suspected it would feel like. Herzog's daffy madman-poet approach to filmmaking coupled with Lynch's stagey, distancing line readings and something-dark-under-the-surface suburban milieus, plus Brad Dourif and Grace Zabriskie cameos. But the further in I went, the less in love I was.

There's definitely something interesting and bizarre and watchable here, and the story of what seems to me like a schizophrenic man being consumed by his bent worldview and possible hallucinations is certainly ripe for a Herzog-Lynch team effort. The problem I think lies almost entirely in the script, which goes to pains to lay out a forced structure that feels artificial almost to the point of parody. On the one hand (and especially when viewed as a pairing with Herzog's other film this same year, Bad Lieutenant) this parodic approach might seem intentional, but where it felt so easy and jabbing in Bad Lieutenant here it feels stilted and, frankly, a little boring. The more Chloë Sevigny and Udo Kier's characters doled out conveniently portioned pieces of exposition and backstory on Willem Dafoe's cop the less interested in the story I was.

Actually, the more I think about the layout and the characters -- like the obvious and pointless cuts in location that accompany each return to the interviews in progress, or Michael Seña as the over-eager partner who keeps trying to enact movie clichés about hostage situations -- I'm certain it's meant to be the hostage-movie formula turned upside down. But it doesn't change the fact that the structure became so tinny and artificial that I was frustrated more than engaged. Bad Lieutenant made cop clichés feel loose and wild, fun; My Son, My Son makes them feel stiff, like an overstarched shirt.

Still, the performances are pretty great, and the Herzogian moments many (and the Lynchian ones, too), and that all makes it worth seeing, without question. That it's loosely based on real events is interesting. (Wikipedia has some interesting details about Herzog and screenwriter Herbert Golder meeting with the man Brad McCullum is based on.) But my first impression is that it's more of a curiosity than a great film. Who knows. I do have the sense this one'll stay with me for a while, and I liked Bad Lieutenant significantly more the second time I watched it. Maybe when I return someday and watch it again, I'll fall in love.