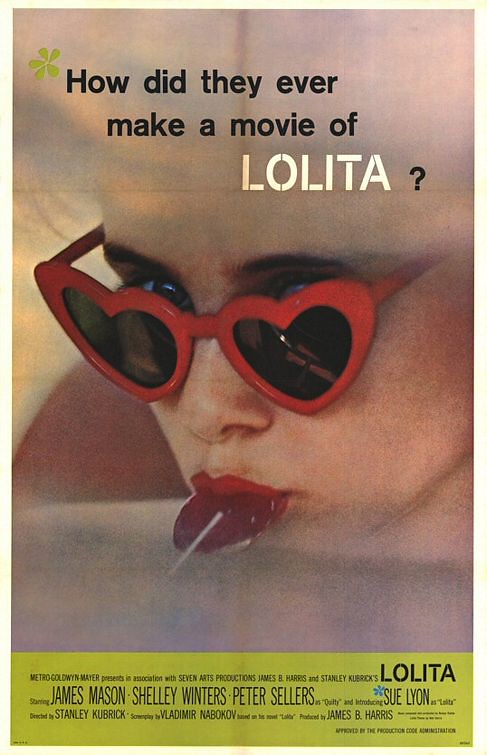

It'd been a long time since I'd seen this, and it's an interesting study in what works and what doesn't. (If I have only a little to say, it's largely due to having just read an excellent piece by Nathan Rabin comparing the two Lolitas, from his book My Year of Flops.)

The film version is unsurprisingly light when it comes to the characters' sexuality and sexual adventures -- no long sequences devoted to Lo's spindly limbs coated in sweat or anything of the sort -- and of course Dolores Haze here is a good deal older than twelve, but the general detached-lust and totally askew protagonist remain, as does the flippant ambivalence of the girl in question. The film isn't shy about the tension between them and even has room for some humorously suggestive bisexual voraciousness from Sellers's Claire Quilty, so you can't accuse the film of being sexless, or even toothless -- just reserved.

What's more interesting are some of the other omissions Kubrick makes as he goes. The most obvious seems to be that Humbert isn't allowed a single moment of genuine joy here (this thought originated in Rabin's book, I confess). The two sequences of Humbert actually having Lolita, both the one first time and the subsequent six months together, are over and done with in a crossfade and some stilted voiceover (for a novel that relies on the beauty of first-person prose, it's odd that the voiceover feels so stiff and formal here -- I can't tell if that's a deliberate choice or the result of it being a post-meddler fix on Kubrick's part). The life of Humbert Humbert is rendered even more pathetic here than in the book, where at least he is his own hero and suffering victim, rather than a petulant, obsessed paranoid-neurotic.

Overall, I like the story all right. It's clearly not the gem later Kubrick movies would be (this one was famously meddled with, as I just alluded to, and I believe Kubrick once said, "If I'd have known how much trouble I'd go through to make it I never would have started the project in the first place."), but it's got a lot of great moments. Peter Sellers plays almost too broad but he's never less than entertaining... though I wonder. It's been a long time since I've read the novel; are we supposed to know that all those "chance encounters" were just Claire Quilty fucking with Humbert the whole time? As it plays in the film, it's so obviously Sellers in those roles that we roll our eyes and wait for our buffoon protagonist to catch up to what is obvious to us every step of the way. James Mason and Susan Lyon and Shelley Winters (here playing a character similar to her role in The Night of the Hunter) are all wonderful. But it doesn't quite escape the shadow of its source material...

Lolita still feels mostly unfilmable, a book about language and perspective and the ability of words to both underline and undermine (see what I did there?), not to mention a study in getting your audience to sympathize with one of the least sympathetic main characters in the history of storytelling. Here I never quite like Mason, though I suppose I do side with him more or less. It's a good go at it, and I'm glad to've seen it again, but it's not a classic, to be sure.