Recently I was discussing the fact that three of the biggest films this year were by Darren Aronofsky, Christopher Nolan, and David Fincher (Black Swan, Inception, and The Social Network respectively), and that all three feel like excessively precise films -- like or hate the films, they're undeniably works by masters of their medium, with a tight, confident grip and control over every aspect of production, from the tiniest of details to the grandest of overarching themes. But their expert precision can be as much a burden as it is a strength. In the 70s people complained that the Hollywood New Wave was the first generation of filmmakers who'd graduated from film school, who'd studied nothing except the language of film, and that for all their intelligence and technical wizardry, their films were more about film than about life -- they were at one remove from the subjects. Well this is clearly the generation of filmmakers raised in the shadow of that previous generation; second-gen film students arguably twice removed. Following consciously in the footsteps of Spielberg, Scorsese, Kubrick, Welles, et al, there's a decided lack of looseness to their work. There is almost no improvisation, or randomness, or organic give-and-take. These are artists telling stories from the mind, not from the heart.

As much as I really liked The Social Network and Black Swan, and mostly liked Inception, they had a coldness to them. But so do the best works of P.T. Anderson, the Coens, Wes Anderson (!!), David O. Russell, Jim Jarmusch. It seems to be the trend, this bent toward precision and control. And for the record, I'm not against it. I just named some of my favorite big-name American filmmakers. But it does feel like a one-sided argument.

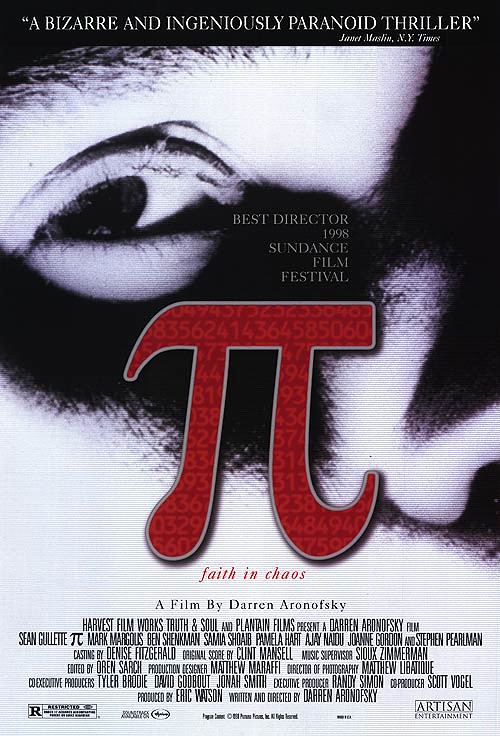

Pi (much easier to type than its greek-letter numerical title) is an argument for the other side. Imprecise, shot guerilla-style on grainy film, somewhat unhinged and never locking down what it's even about. It feels (now) like the bridge between Eraserhead and Primer. One foot deep into impressionistic psychodrama and one foot deep into the obsessiveness of science and math. It's also obviously a precursor for many or most the elements in Requiem for a Dream -- a film where Aronofsky tried out his hand at precise control before loosening up (a little) for the more abstract The Fountain. I wonder sometimes if the poor performance of The Fountain is what pushed him back in the other direction, toward the more linear and... cerebral is pointedly the wrong word here, but let's say controlled storytelling of The Wrestler and Black Swan.

Aronofsky's always been obsessed with obsession (which is maybe why being at one remove from his subjects comes so naturally), telling stories of characters losing themselves to their passions, or their weaknesses, or (often) simultaneously both. Pi is such an impressively audacious, confident first step, even if (partly because) it's a messy, overly abstract, slightly pedantic piece of madman poetry, a deceptively simple story told from a bent, subjective view that should be offputting but never is. Max Cohen is never unlikable, possibly because his weaknesses are so profound and prevalent, because for all his super-genius and arrogance he is pitifully human. It's a good touch, and there's a lesson in writing a strong protagonist here. He has specific objectives, specific obstacles, identifiable and (sort of) relatable weaknesses, and he's doing cool stuff that maybe we all (a generation of geeks and thinkers) daydream about doing. It's not a perfect film, but it's almost a perfect first film.

No comments:

Post a Comment