So we have a trilogy. Dramatically, part one makes a hero (really, a demi-god) out of an ordinary man and sets him up as the chosen one, ready to save humanity from the insidious Matrix and its nigh-undefeatable dark knights (agents). Betrayal from inside almost ruins everything, but thanks to the stalwart faith of our hero's allies, he is able to rise to the challenge and prove himself powerful indeed. Part two lets our hero return "home" to a hero's welcome, and sends our band of crusaders on a series of mini-quests, each putting them one step closer to goals they only partly understand. It also introduces us to a new (version of a familiar) adversary and while Neo and Morpheus and Trinity are busy fighting level bosses like the Merovingian and his twin albino wraiths, Smith's powers expand and the threat he poses looms larger and larger. Part two ends with our hero Neo meeting the archetypal oracle (who is not the Oracle actually, but the Architect) and learning more about his nature, the nature of the universe, and the dark destiny that lays before him -- after all, the ultimate hero's challenge is to deny one's destiny.

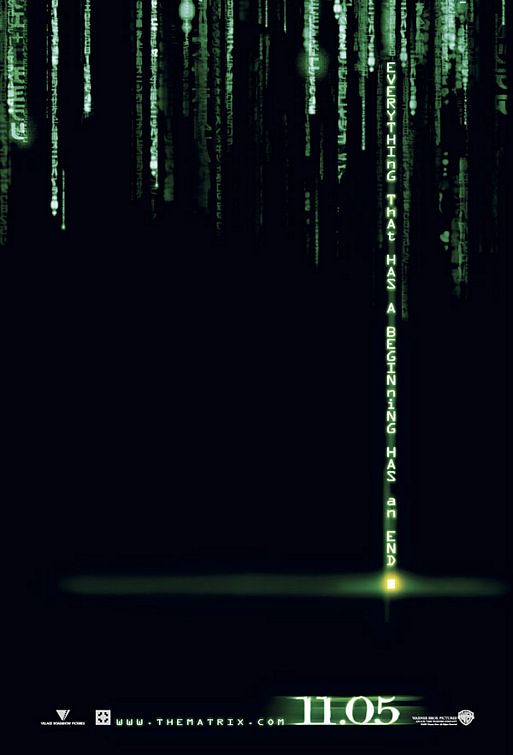

And so we come to Revolutions, part three, in which all the final confrontations occur. The war for Zion is fought, and it's well told, but it's also as close as I need to ever get to a Warhammer 40K movie; Neo confronts his Mentor (in the first film this was Morpheus, but here the role's been usurped by the now misnamed Oracle) and gives the "Ben, why didn't you tell me?" speech; and Smith comes into his own, having grown from evil soldier to evil god in a way that perfectly counterpoints Neo.

The Smith/Neo thing is a nice segue into what I think Revolutions is doing thematically. Seems to me that The Matrix, thematically, is about questioning the given world and exploring the boundaries of what we think of as humanity/society. The Matrix Reloaded passes itself off as exploring the dynamic between causality and freewill and it expands into a more diverse (and possibly muddied) view of agency and sentience. The Matrix Revolutions continues the overarching theme of choice and destiny, and also concerns itself heavily with the idea of balance and dichotomies: an equation has to balance itself out at all times, so the more powerful Neo becomes, the more powerful Smith must become necessarily. (Tangentially, this reminds me of the Star Trek: the Next Generation episode where the computer imbibes Moriarty with superior intelligence, will, and self-awareness because that's the only way he can be a match for Data.)

And here is where Smith would be an interesting study. As with the general tone of the whole trilogy there's nothing subtle about the philosophical musings in the story, nor anything terribly deep behind it all, but that doesn't make it uninteresting to discuss. There are too many ways in which Smith is truly the anti-Neo ("your negative," the Oracle calls him) for me to get into here. One way I find interesting is that Neo is The One (a message pounded into him and us throughout the series) and Smith becomes The Many, drawing his strength from his multiplicity and multipicability in just the way Neo draws his from standing out, being singular. As Neo's powers expand impossibly to exist outside the Matrix, so too does he draw Smith's influence into the "real world." (While this still strikes me as hard to stomach, and makes me wonder if there's not a sneaky "Matrix-within-a-Matrix" thing going on here, I think it's probably easier to accept the magical realism as the point at which prophecy and spirituality rule over one portion of the story, even while science and logic purportedly rule another -- all things in balance, after all.) As Neo's personality evolves from excitable, angry, and nervous to the serenity of a zen master, Smith follows an inverse trajectory from eerie, unsettling coolness to fury, frustration, and childlike (albeit evil) glee. Like I said, too many ways the two are counterpoints for me to go through them all here.

I have to admit that the big action sequences here, including the war for Zion and both encounters with Smith (on the Logos and in the Matrix) are really thrilling, gorgeous, never-boring sequences that justify the big-dumb-fun of the story for me. For my money, despite a couple of nice sequences the second Matrix movie is hands-down the weakest, and while the first is the only one that really works start-to-finish as an elegant and never-unsatisfying story, the third one is admirable and gives reasonably satisfying closure to the series -- I'm even able, after a few viewings, to overlook the weird Freudian/Christian climax and resolution. It may be a manufactured trilogy, but I still like it well enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment