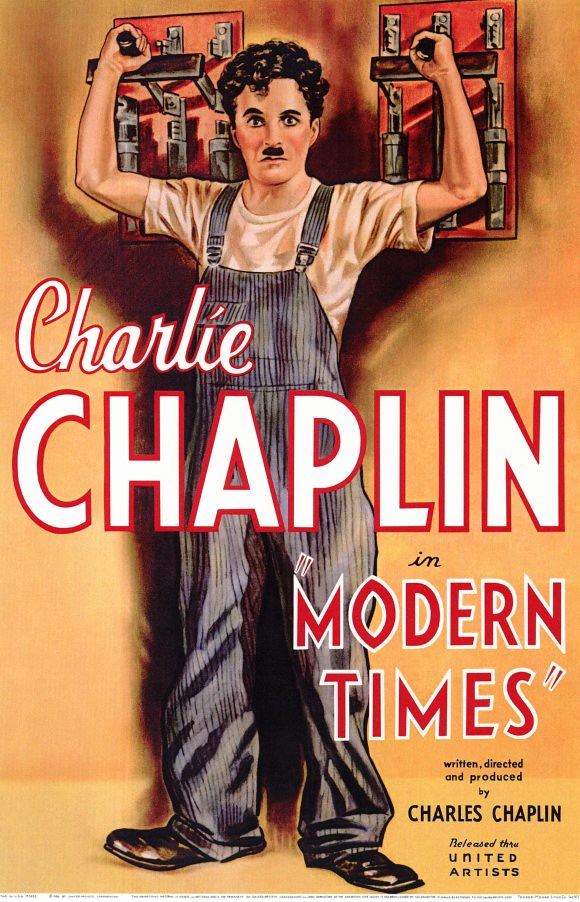

I think there's actually something lost in our savvy culture where film exists as a fully-formed and nuanced language. Early films have a real pioneering energy, where anything is still possible and any story can be told, in any form. The fact that the vocabulary for visual storytelling was still fairly new allowed people like Keaton and Chaplin, Pabst and Lang, to tell deceptively simple-seeming genre-bending tales built on brand-new archetypes and symbolism without feeling preachy. Modern Times feels like mythology more than narrative, and every event is just as pregnant with layered meaning as in any contemporary film by a modern master, but without any pretense. The result feels a lot more subversive, rather than less subversive, as the dancing singing buffoon in the funny hat and baggy pants who spins around and falls down for our amusement is also the guy sneaking in anti-industrialist, anti-socialist messages, whose charming little comedy reminds us that life gives you breaks, but life also never stops throwing you curve balls, so don't relax for a second. It also suggests that crime isn't done by evil men, that unionizing workforces isn't always in the worker's best interest, and remains heartily skeptical about the value of both industry and populist entertainment. It is very humanist, just a story about little people keeping their chin up in a world busily giving and taking away so fast they can hardly keep up. Fate and fortune are capricious, and all you can control is how you deal with it, and who you hold on to.

That's a lot of message for a comedy about a man who keeps getting stuck inside giant clockwork gears, or rollerskating around the lips of chasms inside a massive department store, or making up gibberish songs to appease a restless dinner theater crowd, or constantly destroying the barely-held-together thing he and his love try and think of as "home," only to have her patiently restore each bit as best she can before he causes another catastrophe. The thing is, I can't even describe Chaplin's setpieces without making them sound heavy with symbolism and metaphor, and if I had a complaint at all it's that there are times it feels like we're just waiting for the next big setpiece to arrive. The time between stunts and numbers are the times where the era's adolescence is most starkly felt -- sure, there's characterization, and to a degree it's satisfying too, but it's never as graceful or as meaningful as when the Tramp is actually doing something. Those moments shine on multiple levels; they have me laughing at the antics of clowns and unpacking the imagery of poets all at once.

Now I want to really sit down and revisit Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, see if I react similarly. After all, there's that famous Coke-vs-Pepsi rivalry, and I've got to pick a side, don't I? I'll get back to you on that.

No comments:

Post a Comment