Of course I like this movie. It's such a poetically humanistic movie, relishing in the small pleasures and tiny magical moments of being alive and human. It's not the first time theology or literature has suggested that angels live in awe and envy of mankind (if memory serves, Neil Gaiman's short story "Murder Mysteries" is one of my favorite explorations of this theme), but here it's done so viscerally and with such straightforward simplicity that you aren't simply told that angels envy us, you're shown how and why. At a remove, the angels aren't burdened with the distractions of being human and see the beauty of it instead, tiny inexplicable moments like a woman closing her umbrella in the rain and allowing herself to get soaked, that the angels here call "spiritual moments." This is a cinematic poem to what's so great about being alive.

It's also a story about being "at a remove" from life, of the importance and value in being more than just an observer of human nature, and getting your hands dirty in the muck and mess of it all. It's not nearly enough to sit back and watch, appreciate, admire, ponder; in Wings of Desire the pleasure of cold hands, smoking and coffee, or kicking up sand outweighs the most poetic thought or seemingly transcendent observation. All art falls victim to this distancing, and is therefore inferior to mere life, to mere living, even to suffering or distraction. It's a lesson I fight with every day myself, to be honest, and so again: of course I love this movie.

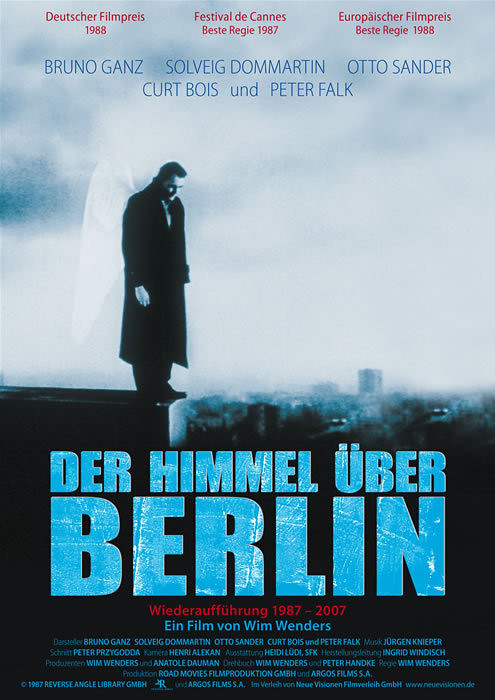

There's not much I can say about it, only because there's so many little things I'd love to say about it. Its use of color, light, performance and photography are all brilliant, intricate, and stunning. The editing especially carries the story as we cut from disparate scene to disparate scene or even intercut an unrelated but beautiful image into a moment. When Marion delivers her monologue at the end to Damiel in the same tone and rhythm as the onslaught of inner voices we've heard throughout, we know that what she is saying carries the weight and vulnerability of truth; she is revealing herself completely in this moment, speaking the language of the secret inner self. The interjections to Cassiel, to Peter Falk (!), to Homer lamenting a changed world, are all profound and perfect counterpoints to the main story of Damiel's fall (and his fall for Marion, so to speak).

The movie always stays with me in a million ways, leaving me wondering about life, the universe, and everything, but this time I'm also left with a strange thought: [SPOILER] if Peter Falk fell from grace as an angel twenty or thirty years ago, then who is the grandmother he is thinking about when wandering the wrecked plaza and seeing "the station where all the stations end"?

No comments:

Post a Comment