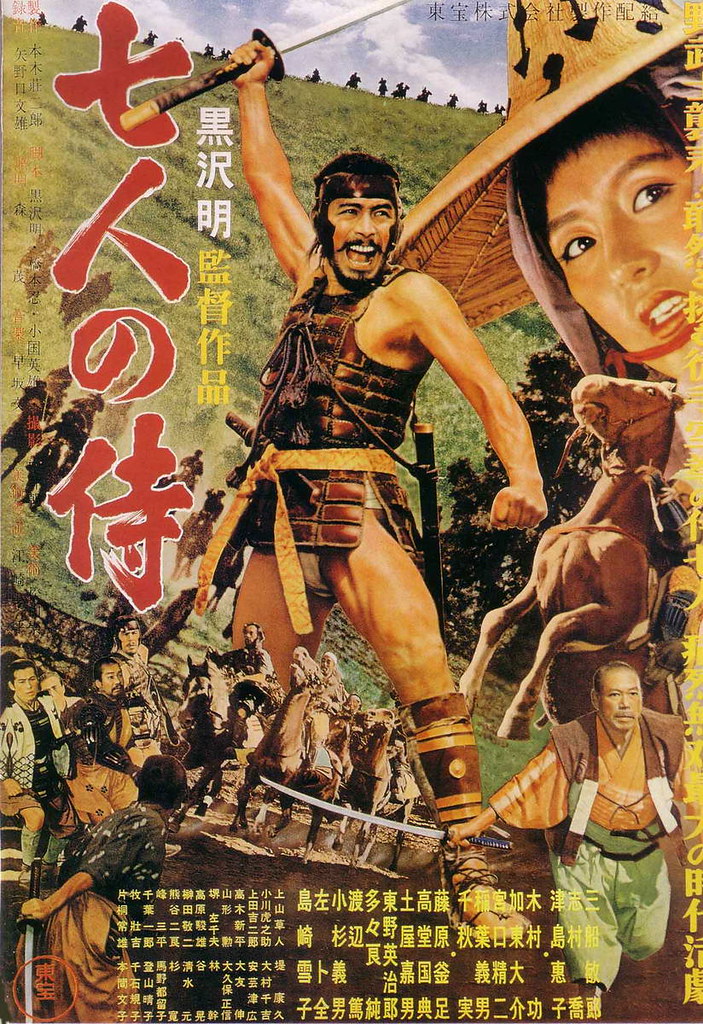

This got watched in two parts with almost a week between, split in half right at Intermission, but I had the pleasure of watching it with someone who'd never seen it before. Plus, it'd been a long time since I'd last seen it, so all in all I was watching with fairly fresh eyes. The movie splits easily into three parts, each roughly an hour long: act one is rounding up the samurai, act two is preparing the village for attack, and act three is the battle itself. For the most part it does well keeping clear its large cast and crucial-to-the-story geography, though I admit a couple of times someone would get shot and one of us would turn to the other and say, "Wait, which one was that?" (It was almost always cleared up for us in the next scene, however.) Much of this is due to Kurosawa's choice to stay wide during fight scenes, even when it's a single character out of the crowd we are meant to be concerned with. I'm not criticizing this choice, because keeping it wide allows the sheer physicality of the performances to carry much more excitement than cutting into close-ups could sustain, but the result is sometimes all those frantically moving Japanese men in period outfits blur together. So it goes.

I also really enjoyed how clumsy both sides got during the final battle -- the attempt to waylay a horseman would fail, and the villagers would have to chase desperately after a bandit into the village, but then the bandit would have trouble controlling his horse because of the chaos of the battle. It felt kinetic and unrehearsed and gave both sides an amateurish quality akin to realism. And of course Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune) proving with every scene exactly why he'd never be a samurai and yet why he deserved that honor just as much as the nobler, better-trained warriors he fought alongside. That he was given a samurai's gravesite without a single word spoke more to the respect that he'd earned than any long monologue ever could have. Allowing the story's biggest beats to be conveyed visually in the background of a scene is a strong choice for a film of any era, but it pays off because it challenges the viewer to put it together himself: it all goes back to the old adage that showing is more impactful than telling.

I know I just focused entirely on surface, fairly obvious cues from one of cinema's most famous and thematically rich films, but it's late and I haven't watched it in a while, so forgive me that. I actually intend to return to the two Criterion commentary tracks (something I don't do often enough), and if I feel like I have enough to say about it, perhaps I'll make a post about their viewing as well.