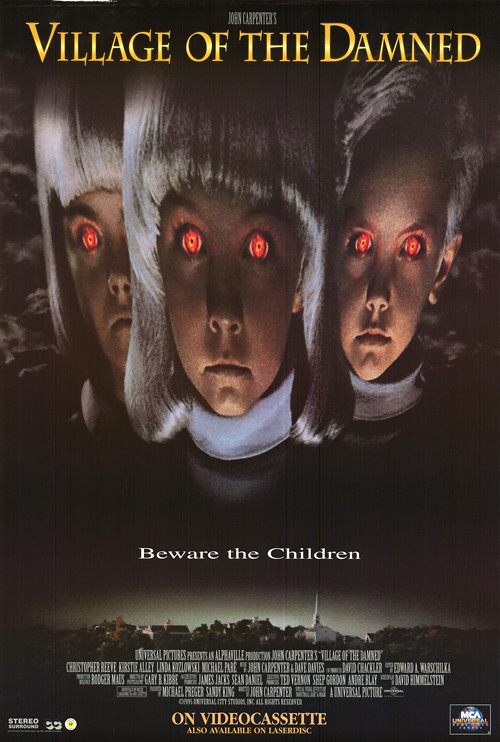

It's funny because even though I really liked the 1960 version of this, I also imagined it could be remade a little darker, a little tenser, and with more in-depth characterization. Watching John Carpenter's 1995 version is like a cautionary tale to remakes. It has a bigger-name cast (Christopher Reeve! Mark Hamill! the woman from Crocodile Dundee! uh, Kirstie Alley!) and sharper effects (the eyes are never weirdly off-center), and it's got a more tense ticking-clock climax (literally), but overall it feels a lot more clunky, forced, and staged. Whatever magic made the original move smoothly and feel like a steady downhill slope into creepy land has been sucked out of this version.

The truth is, John Carpenter films tend to be group-protagonist stories about what happens next, and almost never about who it's happening to. I like stories to be about the who at least as much as the what, and Village is, I think, a story that wants more than most to be about individual characters. Mark Hamill's preacher who turns sniper is one example of a great dramatic evolution that wasn't given much due. But even more than that, this version spends too long spinning plates in the middle. The kids do their glowy-eye-thing and force people to do things against their will, and they do it first as retribution and then ultimately as self-preservation, and yet people keep pissing them off in basically the same ways (an accident, a taunt, a threat) and they react in basically the same way (glowy eyes, offender hurts or kills themselves in whatever way is both most convenient and suited to the nature of the offense). Once or twice this is scary, but then it keeps happening, and we don't even get a quick-cut shorthand version; each time we watch the full sequence with the glowy-eyes, the music, the zooms, the struggle not to off yourself, and finally bang, suicide. The repetition feels a little exhaustive and doesn't help keep the suspense up.

I would still like to see a version that exploits how the children take for granted that they can read your thoughts and that you are trying to stop them. All encounters needn't end in death: they could simply mind-warp you into defusing bombs or unloading guns when you tried something, and any conspiracy against them, they would know about and be able to circumvent. Then more time could be spent in the uncomfortable position of interacting with them, exploring the hivemindedness of them, and facing the unstoppable threat of someone who can control you if they have to and knows your every thought. In both versions, the scenes of the one "trusted" man trying to get through to them -- to simultaneously educate them and learn about them -- are the best scenes. It'd be easy to keep the dread up while building on those, I'd think. Neither version quite goes this direction, but both touch on it. (A common theme in my critiques: "Hey, this movie started to go in this interesting direction but it had something else on its mind and went elsewhere instead. I want to see a version that goes in that other direction instead.")

In the end, this is not a bad film, but it's definitely inferior to the 1960s version, and there's just no getting around it. But it feels definitively Carpenterian; in fact it's easy to see this as the final part in a loose trilogy that includes The Fog and The Thing -- though I do like The Thing quite a bit more than the other two.

No comments:

Post a Comment