I'd heard a lot about this film for its dialogue, for being a famously left-wing script that didn't pull its punches. I knew it was a noir about newspapermen. I knew it got compared to Network. I hadn't really thought about that, though, in the terms this presents them: anti-heroes that are newspapermen, as basically slick-talking amoral schucksters and underworld power barons. Actually, I've been reading about other stories that do this, like two Fritz Lang films, While The City Sleeps and Beyond A Reasonable Doubt, so it's not like there's not precedent here -- and in fact, those films were 1956 and 1957 respectively; since Sweet Smell is 1957, clearly something was in the air.

But this isn't really a noir at all. For one thing, the story pointedly lacks femme fatales, and the only woman I can remember in the entire film who wasn't a cowed victim or means to an end (which, in this world, is worse than merely being a "cowed victim") was an older woman long since accustomed to her dubious husband's wandering penis. For another, the anti-hero of the noir is almost always someone able to step through the muck of the underworld and come out clean -- a man whose principles and convictions allow any number of questionable deeds because he knows the ends justify those means. Here the ends are the dirtiest part, the protagonist has to have a last-minute "change of heart" because he hasn't had a straight and true noble purpose from the beginning. This is a story of moral awakening, with innocent people (noir stories generally don't even have innocent people) hurt by terrible people, and that's all good. I'm not disappointed that this isn't a noir -- I don't think it should be -- but it seems to have been miscategorized, if you ask me.

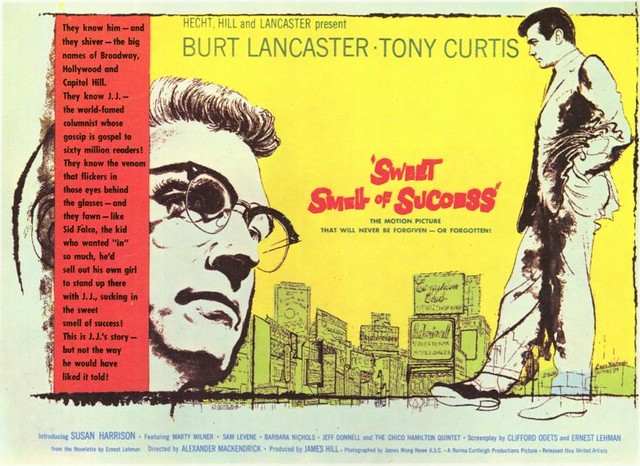

So, sharp-as- and fun-as-hell dialogue, check. The city at night, seething with corruption, check. Fascinating anti-heroes and an alluring world of ugliness, check. Noir trappings -- well, no, but that's okay. But what isn't covered in all of that, that I hadn't expected, was the nuanced and exciting kind of antagonist/villain that this film has. Burt Lancaster's J.J. Hunsecker is wonderful. His introduction is beautifully orchestrated, giving him a practically mythical element (coupled by his story of loving-his-sister-just-a-little-too-much). He's intimidating and every bit believable as a powerful man with the power of will and the ivory-tower separation from the common man that makes him both a pitiable king and an amoral monster.

[SPOILERY NOTE: There was a point very late in the film after Susie had attempted to throw herself off a balcony and Sidney had managed to wrestle her back in. J.J. attacks Sidney, seeming to misconstrue the situation, in fact perhaps knowingly choosing his beloved sister's obvious lie over his dirty-handed minion's more feasible story. (Sidebar: Lancaster is intimidatingly huge; it worked so well for the character in general but it was also great to see that physical threat made manifest, especially on such a deserving scoundrel as Sidney but for all the wrong reasons, fittingly.) In his defense, shouting anything he can to stop the attack, Sidney blurts out that J.J. is behind the framing of Susie's lover. There is an eerie moment -- Susie stands with J.J., no longer sure which side to take here. J.J. turns to her and says, "It's a lie, Susie. Just as I know he lied to me about your suicide attempt, you know he's lying to you about my involvement." Susie obviously knows her suicide attempt was genuine, and for just a moment this invitation to exchange willful ignorances hangs there, and part of me really wanted Susie to agree to it, to sink into the quicksand and say, "Yes, of course Brother," and together they would destroy Sidney, put it all behind them, and rewrite their history fully. That end -- Sidney dying (or being run out, or locked up, or whatever) and Susie selling her soul to stay at her brother's side -- would have been so dark I think it would have been unsatisfying, ultimately, but there was a moment there where I wanted to see how it would play out, how dark could this dark story get, and would it dare?]

I don't think of the 50s as an era with layered characters exploring moral gray areas (or at least making your audience sympathize with characters firmly entrenched in the black, say). I guess audiences didn't either, from what I read about the initial audience response to this. Critics loved it, though, for all of its sharp-tongued intelligence and emotional messiness, and, not surprisingly, so did I.

No comments:

Post a Comment