I've been reading the Complete Peanuts books lately and in a strange way have fallen in love with them, an impulse I had because so many respected writers and artists I know speak so lovingly of them, and because I'd remembered from a couple years back discovering that the Charlie Brown cartoons aren't funny but painfully, unsparingly melancholy. The comics, even more so. By the '60s it feels almost like Charles Schultz is no longer trying to be funny. I think he knew that nostalgia for a certain kind of childhood anxiety and emotional despair was plenty charming on its own. And I think he is right. There is something weirdly beautiful about Charlie Brown's endless, year-to-year cycles of the same kinds of pain, and Linus's neuroses, and Lucy's fussiness, and Snoopy's fantasies, and Schroeder's borderline-autistic love of music.

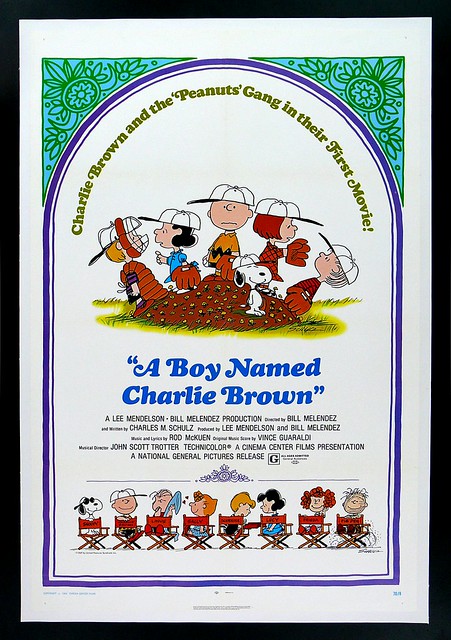

Halfway through rewatching it, I described A Boy Named Charlie Brown as "the unrelenting psychic dismantling of an over-anxious all-around failure, played as bittersweet nostalgia." Scene after scene we watch Charlie fall apart. He can't fly a kite. He can't manage a baseball team (or pitch). Lucy shows him a slideshow, categorizing and illustrating in painful, traumatic detail every single fault within him. Even when trying to cheer him up, Linus can't help but beat Charlie Brown at tic-tac-toe. Charlie Brown says he is a "born loser." Linus convinces him to join a spelling bee, and a couple of lucky words gets him past the local and state tournaments and into a national competition, where he agonizes over spelling rules, loses sleep and becomes a delirious wreck. When finally excelling at something, he finds he is more miserable than before.

Then of course, all that minimal success and popularity (even the other kids tune in to see, and after his own mini-crisis with a misplaced loaned blanket is resolved, Linus sits in the front row with Snoopy, eager to support his friend) is just a build-up for an even bigger failure than he's ever experienced before, as Charlie makes it to the last two spellers and blows it on the easiest word, the breed of his dog. He spells "Beagle" as "Beagel" and loses, in front of everyone he knows, when he was right there and could have had the trophy.

The spelling bee itself lasts about sixty seconds. The drive home after losing lasts something like five minutes, followed by Charlie walking the empty streets, Charlie going into his empty house, Charlie undressing and crawling into bed -- where he remains through the whole next school day and after. There is no question that this is being milked for all its poignancy and pain, basking in the miserable afterglow of failure. Linus comes to try once again to cheer up his friend ("We played a baseball game without you today; it was the first time we won all season,") and finally all he can say is, "Well, I can understand how you feel. You worked hard, studying for the spelling bee, and I suppose you feel you let everyone down. You made a fool out of yourself and everything, but did you notice something, Charlie Brown? The world didn't come to an end." It's the best he can offer, and it's enough to convince Charlie to get out of bed, get dressed, and go out.

Wandering by friends at play (mostly ignored) he goes to the baseball mound and kicks up dust. And from there he sees Lucy, her back turned, goofing with the football. He creeps up on her, momentarily confident all over again -- hope springs eternal -- and rushes her for a kick. But -- yank! -- Lucy was ready for him, and he goes flailing and crying out in true Charlie Brown fashion ("Auuughh!"), and lands unceremoniously on his ass. Lucy comes up to him and says, sort of sweetly, "Welcome home, Charlie Brown."

You fail at everything, Charlie Brown, but look on the bright side: your friends are still there to tease you, and there are always more opportunities to fail ahead. (In one strip, Charlie Brown tells Linus, "I've come up with a new philosophy: now I only dread one day at a time.") Children's humor doesn't get much blacker than Peanuts, and this film is a perfect, unapologetic example of that. The closest thing to a happy ending in Charlie Brown's world is the recognition that nothing has changed, even when he fails so spectacularly as this.

The thing is, I don't find any of it depressing, and I don't revel in the depression of it. I find it all enlightening, and even a little energizing. Not to get all hippie-deep on you, but: That's life, man, you know? Not to get all existential-nihilist on you, but: Life will continue to be absurd, cruel, and kick you when you're down, and your only choices are to get up or lie still, and neither will drastically change what happens next (life will continue to be absurd, cruel, and kick you when you're down), and so you might as well get up. Reading Peanuts and watching this (and, if memory serves, its successor, Snoopy, Come Home), I am reminded of one of my favorite Kurt Vonnegut quotes: from the underrated Timequake. When Vonnegut wonders to himself "Why bother?" he comes with this response: "Many people need desperately to receive this message: 'I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people do not care about them. You are not alone.'"

Again, not to get all touchy-feely about a late '60s cartoon based on a popular newspaper strip about a bald little boy who sucks at everything, but: What can I say? There's something thoroughly grand and humanistic in this, a certain emotional and dramatic territory and language that gets almost no attention in the funny-pages or in children's cartoons. How could I not love it?

No comments:

Post a Comment