I took Japanese in high school, because it was offered and Spanish, French and German all sounded boring by comparison. Within the first week, my freshman year, they made us choose Japanese names that we would keep for as long as stayed in that program (I and my friends did all four years). Off a list of names I chose Shingen before I could even read it, because it looked easy to write in hiragana. Later our Sensei explained to me that Shingen was the name of a famous Japanese general. When we had to pick fake last names and play-act various language lessons with full names, she practically insisted I choose Takeda, because that was Shingen's name. So for four years, I actually answered to "Shingen-kun" or "Takeda-kun." All I knew was, this was something like the equivalent of an ESL student deciding to call themselves George Washington.

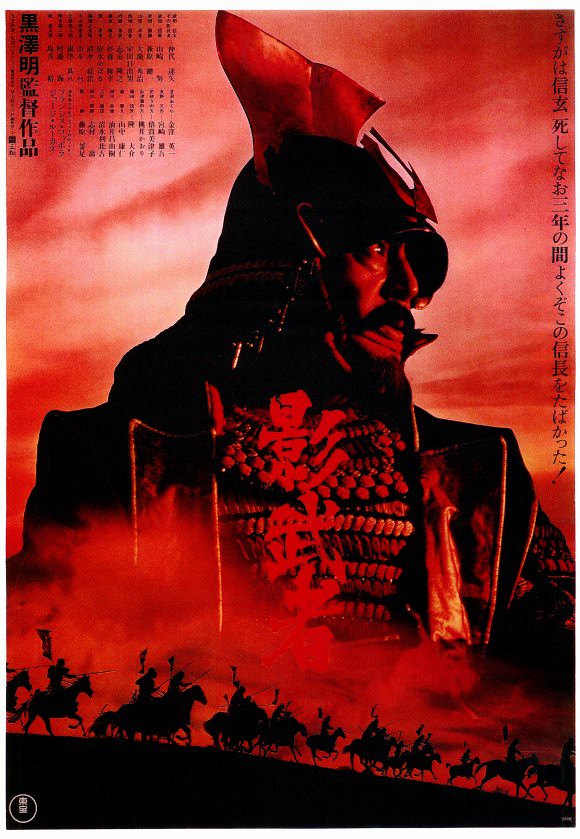

Kagemusha is the story of the last days of the famous Japanese warlord Shingen of the Takeda Clan, and now it's 15 years later but I still think of "Shingen" in the back of my mind as some kind of name associated with me. This has no bearing on anything, other than novelty and coincidence, but I wanted to share anyway, since it was in the back of my mind as I watched Kurosawa's epic. (Also, she did a pretty terrible job explaining to me Furinkazan, but perhaps she should get props for even trying, considering she wasn't a history teacher and was barely a language teacher. I was surprised and excited by how clear Kagemusha makes the concept, and also how central it is to the philosophy of the story.)

The story is an epic war movie, with larger-than-life characters and events, massive battles and hundreds of armor-toting, horse-riding extras, but it's surprisingly philosophical (surprising for a war epic; not surprising for a Kurosawa film). It's also, appropriately, the dramatic story of tragic characters in tragic times -- including Takeda himself, his brother/double, the rescued thief who becomes his Kagemusha ("Shadow Warrior," or professional impersonator), many of his generals, and even his young grandson. Each of them suffers in one form or another for the "greater good" of maintaining the Takedas' strategic foothold in an unending three-way war.

I'm pretty sure you can chalk this up to the drastically alien time and place, but it was interesting to watch a film literally about war and not feel turned off by the war-porn nature of it. In fact, I found the notions of honor as depicted in the film to be attractive, and admired the men in many cases. Takeda's enemies, for one, refused to feel joy at the loss of their most dangerous adversary out of respect for the man, and the loyalty felt by Takeda's generals led them to kowtow to an impersonator for three full years after his death. Then again, even the Kagemusha himself was so moved by the power of the man's shadow that he found himself willingly playing the role and continuing the legacy.

That's, I think, what Kagemusha is really all about: the "shadow of the king," the way a great man's reputation can outlive him and as if by sheer inertia continue propelling people down paths he's willed for them. Their enemy's "bravest general" turned back willingly and unhesitatingly at the very sight of "Takeda" sitting atop the hill, as immovable as a mountain, and his personal guard gave their lives just as willingly and unhesitatingly to the very idea of the man, standing in the way of incoming arrows to protect a common thief who stood only as symbol of the once-great, beloved and feared Lord Shingen.

But on the other hand, we see all too clearly (and anticipate for over half the film, which adds some great tension) how easily that same legacy can crumble the moment your followers lose their faith in your legacy, as in the end (the ruse is exposed by such a fleeting accident, when the lord's horse bucks the well-meaning impostor) Takeda's son Katsuyori seals the fate of the entire clan simply by "moving the mountain." His impetuous need to prove himself more than just an unloved son standing in the shadow of a great man unraveled the quaking fear and grudging respect their enemies had for them, after which each aspect of Furinkazan fell one by one, systematically: the speed of the wind wasn't enough, nor the silence of the forest, nor the ferocity of the fire -- not without the undefeatable mountain behind them. The moment Katsuyori moved the mountain, everyone knew, the magic was gone. There was no shadow to stand within, and that was all that held the Takeda Clan together.

An interesting and somewhat conservative message which I can accept as beautiful and noble within the confines of the story, even without knowing if there was anything the warlords fought for beyond power and borders (that is, ideology doesn't matter here; war is simply the thing you do if you're a warrior). But if you transport this message into twenty-first century terms, it's actually kind of appalling. Honor and pride and military might are things that can be moving when the world feels like a fantasy -- knights and dragons, samurai and musketmen, even the Klingon warriors from Star Trek (who to be honest I found myself reminded of more than once, since I've been watching a lot of Star Trek lately). So really, I'm glad for stories like this, because honor and nobility are such daring and bold subjects, and you would never be able to get me to sympathize with a modern-day story of war and great generals -- at least not in the same way.

This is a great film that runs three hours long and splits its time between massive battle sequences and conferring generals and warlords (real and faux) gnashing their teeth, but it's never boring for a second. Plus it's beautiful, both in its photography and its characterizations. It makes me eager to seek out Ran and Throne of Blood, two Kurosawa samurai "classics" I've yet to see.

Soon, maybe.

Seen at Cinema 21.

No comments:

Post a Comment